Demand for Healthcare and Health Insurance

Overview

- One of the central health economics questions: what does health insurance do?

- Early literature focused on effects of health insurance on healthcare utilization (ex post moral hazard)

- Another way to phrase the question: How much should people have to pay for healthcare?

- To answer this, we need to know the effects of different forms of insurance on healthcare utilization

The RAND Health Insurance Experiment

(see Aron-Dine, Einav, and Finkelstein (2013) for a review)

Setup

- Partnership with RAND corporation and team of health economists in 1970s

- Key question: If people pay more for healthcare, will they use less?

- Randomized 2,000 households into groups:

- free-care plan

- high-deductible (up to $5,500 in 2023 dollars) with full-insurance afterward (really an out-of-pocket maximum)

- different co-insurance rates in between (95, 50, 25, mixed)

Setup

- Experiment ran from 1974-1981, cost of $410 million (in 2023 dollars)

- RAND was insurer, collected all data on healthcare used

- Physical exam at the end of the experiment

- All data available now for researchers

Analysis

\[y_{it} = \lambda_{p} + \tau_{t} + \alpha_{lm} + \varepsilon_{it}\]

- \(i\) denotes individual and \(t\) denotes year

- \(\lambda_{p}\): plan fixed effects (main coefficients of interest)

- \(\tau_{t}\): year fixed effects

- \(\alpha_{lm}\): location, start-month fixed effects (randomization was by start month)

Results: How Much Healthcare?

- Free care plan families used $2,000 (in 2021 dollars) in care

- High-deductible plan families used $1,600 in care

- 20% increase in healthcare utilization for free care plan

- Commonly cited -0.2 price elasticity of demand for healthcare

Results: What Type of Healthcare?

- Provided medical documentation to panel of physicians

- Assiged care as highly effective versus rarely effective

- High-deductible plan families:

- 30% less highly effective care

- 30% less rarely effective care

- Conclusion: higher prices lead to less care across the board

Results: Health Outcomes

- No significant differences in health outcomes on average

- Patients with chronic conditions were worse off in high-deductible plan

Threats to validity

- Valid randomization (not really an issue)

- Adverse selection in participation (could be a problem)

- Reporting of claims (some minor concern)

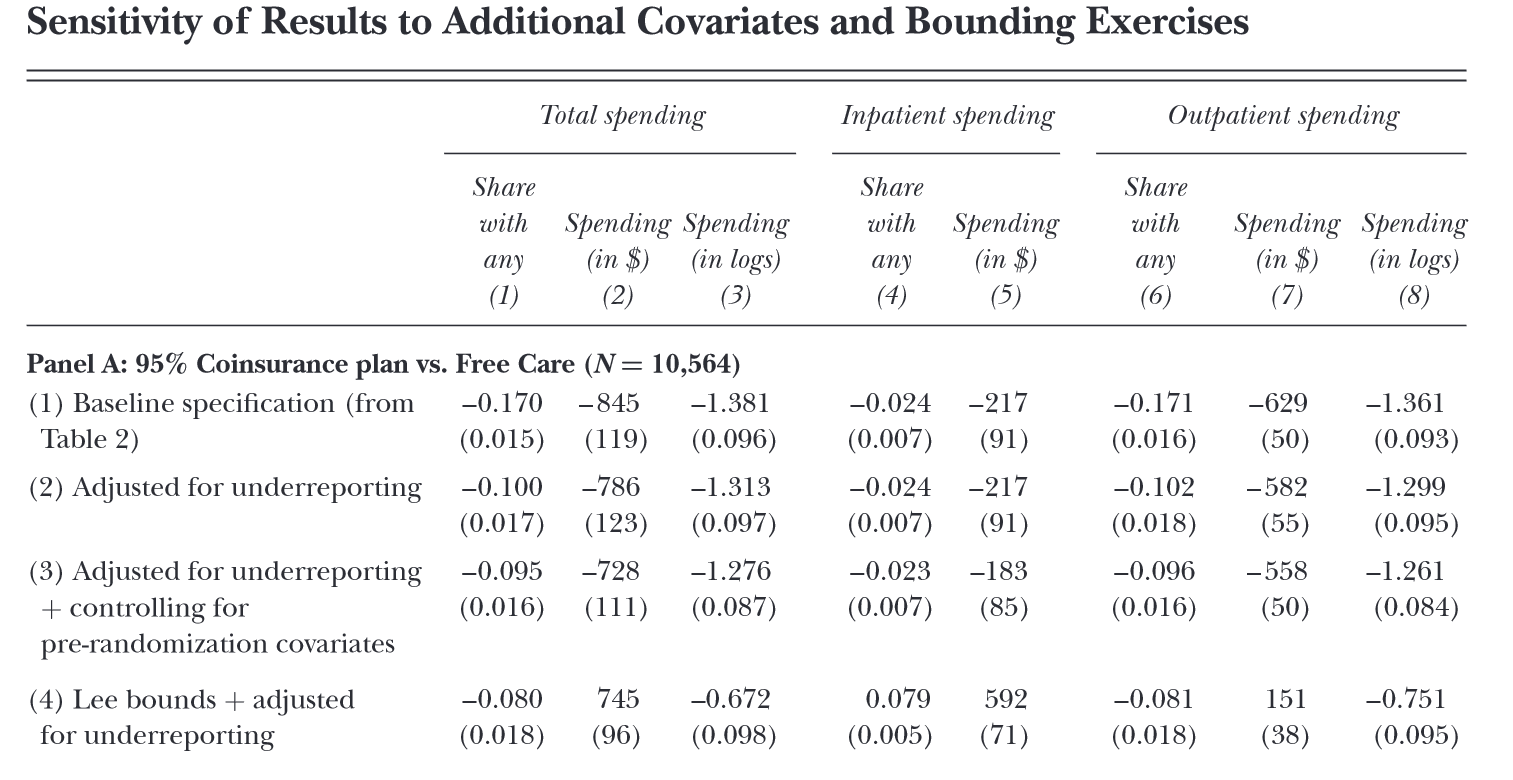

Results with adjustments

Elasticity estimates

Commonly cited -0.2 price elasticity of demand for healthcare comes from:

- Step 1: intensive vs extensive

- Group care into defined “episodes”

- Find no relationship between price and utilization within episode

- Focus on extensive margin (presence of an episode)

Elasticity estimates

Commonly cited -0.2 price elasticity of demand for healthcare comes from:

- Step 2: spot vs future price

- Compare episode rates among those close to hitting OOP max versus those already over

- No difference in episode rates

- Conclude that spot price matters

Elasticity estimates

Commonly cited -0.2 price elasticity of demand for healthcare comes from:

- Step 3: calculating elasticity

- Limit sample to part of year where people are far from OOP max (around $500)

- Calculate arc elasticities for each care setting and for different plan types

- Many estimates ‘around’ -0.2

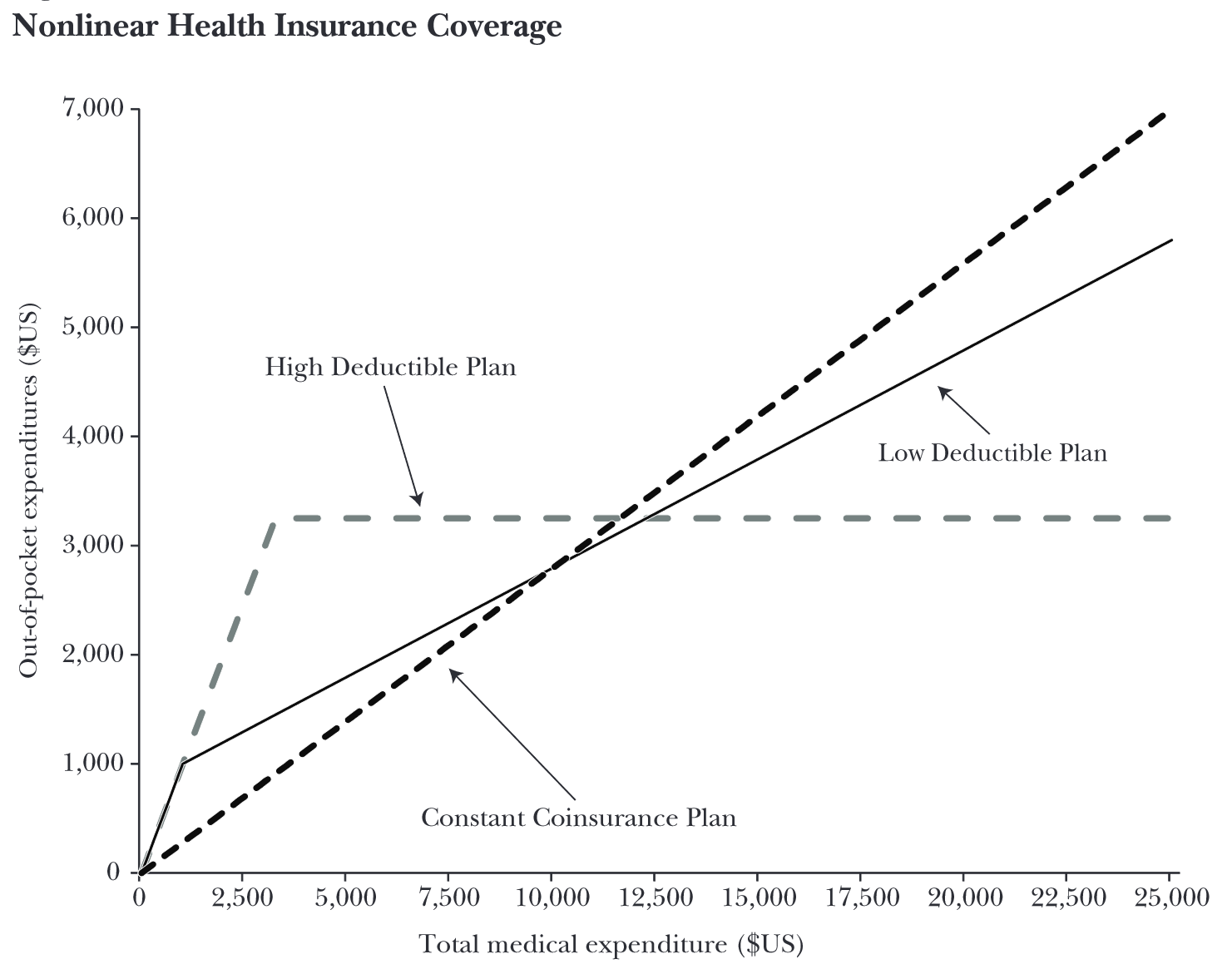

Problems with elasticity applications

How should we predict the response to price changes in a nonlinear pricing environment when we only have a single price elasticity estimate?

Problems with elasticity applications

- Budget neutral in that each contract has same costs to insurer for same distribution of healthcare utilization

- Different assumptions on how to reduce plans to a single average price yield very different predictions (factor of 2)

Key takeaways

- Confident that price matters in healthcare (i.e., people respond to higher prices by reducing healthcare)

- Less confident in the magnitude of the response

- Difficult to apply single elasticity estimates to nonlinear pricing contracts

The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment

(see Finkelstein et al. (2012) for a review)

Setup

- Oregon expanded Medicaid in 2008

- 90,000 people applied for 10,000 slots

- Randomized lottery for slots

- Nearly 36,000 selected for lottery, 30% enrolled

Analysis

- Compare outcomes of those with insurance to those without

- Use lottery selection as an instrument for insurance coverage

Analysis

\[\begin{align} y_{ihj} &= \pi_{0} + \pi_{1}Ins_{ih} + \pi_{2}x_{ih} + \pi_{c}V_{ih} + \nu_{ihj} \\ Ins_{ih} &= \delta_{0} + \delta_{1}Lottery_{h} + \delta_{2}x_{ih} + \delta_{3}V_{ih} + \mu_{ihj} \end{align}\]

- individual \(i\) in household \(h\) for outcome \(j\)

- \(x_{ih}\) are covariates that are correlated with lottery sign up

- \(V_{ih}\) are other covariates thought to be correlated with outcomes (for increases in precision)

Main results

- 2.1 percentage point (30%) increase in the probability hospital admission

- 8.8 percentage point (15%) increase in the probability of taking any prescription drugs

- 21 percentage point (35%) increase in the probability of having an outpatient visit

- No change (but wide confidence intervals) in ED visits

- 0.3 standard deviation increase in reported compliance with recommended preventive care (e.g., mammograms and cholesterol monitoring)

- 6.4 percentage point (25%) decline in the probability of having an unpaid medical bill sent to a collections agency

- 20 percentage point (35%) decline in having any out-of-pocket medical expenditures

- improvements in self-reported physical and mental health, overall well-being, access to, and quality of are

References

Aron-Dine, Aviva, Liran Einav, and Amy Finkelstein. 2013. “The RAND Health Insurance Experiment, Three Decades Later.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (1): 197–222.

Finkelstein, Amy, Sarah Taubman, Bill Wright, Mira Bernstein, Jonathan Gruber, Joseph P Newhouse, Heidi Allen, Katherine Baicker, et al. 2012. “The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127 (3): 1057–1106.